paper • 112 pages • 17.95

ISBN: 978-1-961897-62-5

eISBN: 978-1-961897-63-2

September 2025 • Poetry

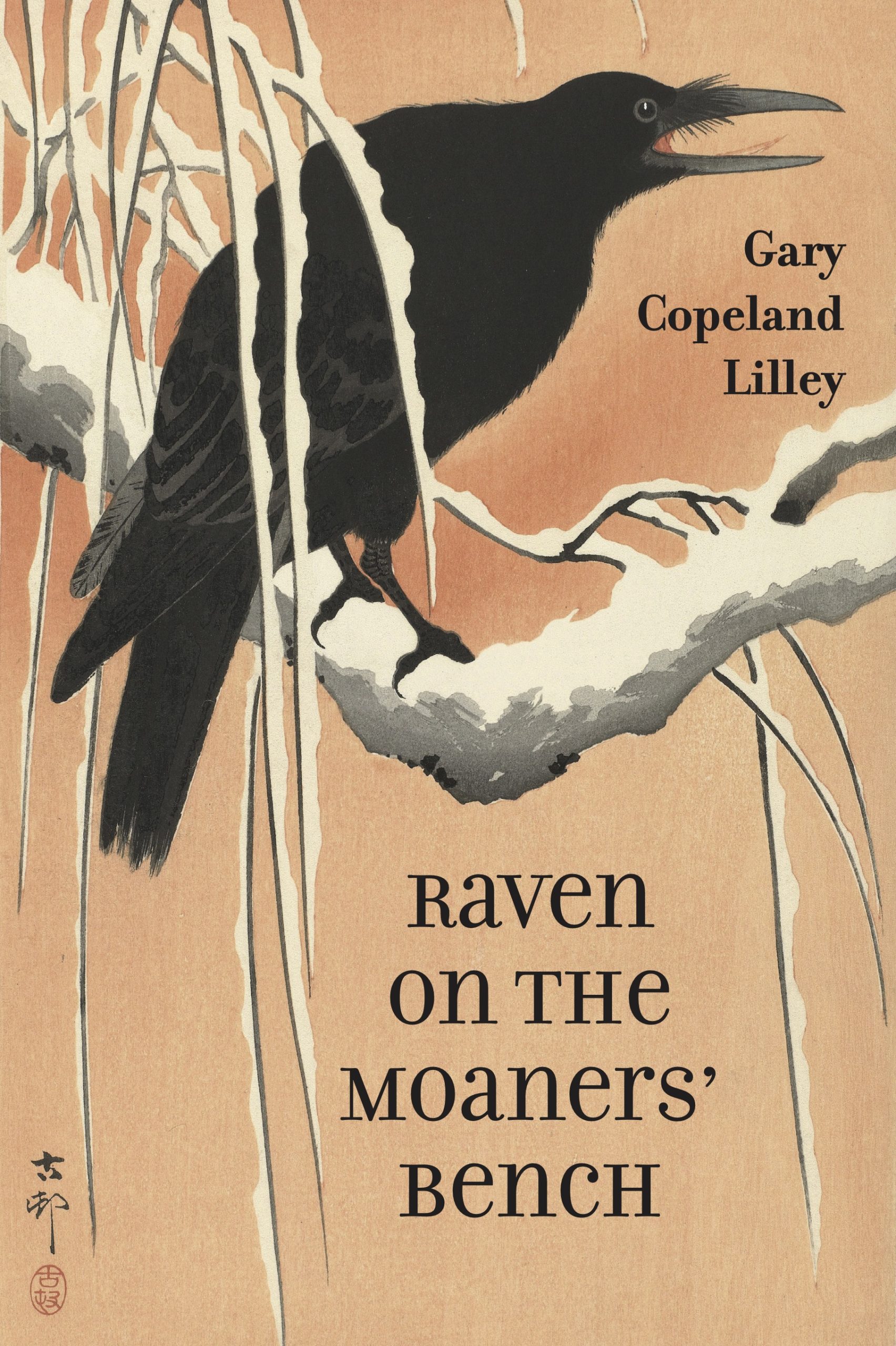

With its titular nod to the most ominous bird in literature, perched on that first pew reserved for mourners, Raven on the Moaners’ Bench locates itself within the oceanic canon that grapples with loss and within the rich history of Black letters, marking a staggering achievement in both. Simultaneously generational and personal, these poems encompass the boundless record of racial injustice in the United States while honoring the particular stories — the irreplaceable personalities, memories, and voices — of each individual life. Lilley memorializes familiar figures, martyrs, and strangers as he speaks to his dead younger brother, to Trayvon Martin, to Freddie Gray, and to two men he is “grateful for but [has] never / had the occasion to know” — two men whom he remains aware of because they are, like him, among “the only four black men / driving these Victorian streets” where “the same cop” pulls them over repeatedly. The sundown specter here takes form as an officer of the law, but these lyrics inventory the many shadows twining over the long road Black Americans have walked in the last four centuries. Lilley casts his words between realms, turning back for Jeff, the brother disabled by a drunk driver at 19 who spent an estranged and troubled adulthood away from his family, who “died long before he actually did,” vaulted into a maelstrom of mental illness and structural neglect after his accident. Laying these poems at the moaners’ bench as “audible expressions / of spiritual need,” “of bodily reaching / toward the lifting away,” Lilley testifies to the burden of suffering he, his loved ones, his ancestors, and his peers have carried. And then he releases it from where he stands, graveside in his psychological landscape, beside his brother lain down “against / a wilderness of hope.”

Raven on the Moaners’ Bench writes into grace, opening an exit from a violent cycle, making possible a lighter future while refusing to forget this country’s incalculable debt. The inward searching and cross-country migration that Lilley’s family, and many other African Americans, have experienced several times in their own histories form the desire for a livable place where safety and opportunity coincide. Jeff walked across America, all the way to the Pacific Ocean, only to die sleeping outside in Los Angeles; this book bears witness to that desperate pilgrimage. Addressing Jeff, Lilley pens a requiem for roadkill he encountered “in a Northwest pathway of [his] own / migration, far from [their] Southern roots”: “I offer up the sacrifice of one doe sprawled / in the what-was-left-of-her on the pathway / where I had to meet her and bring her away / to show you I understood something of how / you bore a terrible cost for our family, / for this unholy country, a cost for which / I won’t allow any repayment / by words, not mine or anyone’s, / on any unstained page.”

From Raven on the Moaners’ Bench

February 26, 2012, the Blood Moon

for Trayvon

I’m a slow old man on the sidewalk,

crown of my ballcap pulled low

over my dome, the complaining crows

that roost on the powerline across

the street are angels in the gloam.

As sure as a hooded sweatshirt

can keep you warm in winter,

the leaned-on car horn heralds

like a newspaper the trauma we fear,

all the way back to the slave ships,

the bloodline. The crows call

to family alive and dead, a dreadful

red moon, the murder of a black boy

in the early evening just living

in his own skin, carrying a bag

of Skittles and a bottle of sweet tea.

Gary Copeland Lilley’s moving, no-bullshit new collection is populated by factory workers, drinkers, long-haul truckers, church moaners, a violent father, a disabled brother whose accident at nineteen took him “into a life where the street/was all I had.” Raven on the Moaners’ Bench is a testament to the struggles of Black people who, like Lilley, know that “this is a world/that wants to rake my tongue/from its river-bottom truths,” and his poems sing to us with the searing eloquence of the real, down-home blues.

Gary Copeland Lilley sings into us what it’s like to be Black in America—safety impossible to gauge, dangers that spire up deadly anywhere. His alchemy is to make deepest pain a potion, a balm, an instigation spiked with reckonings and carrying the ferociousness, the white-hot passion of the unrelenting song. He embodies with wide-open say-anything-wild brilliance, the voice of his dead schizophrenic brother Jeff who claims a central fugitive power in this nomadic saga of a North Carolina death on the streets of LA. We witness the prayer-driven excavation of a family unable to contain the loss of its most needful member. Jeff is Lilley’s unforgettable Lazarus—mouthpiece for the human heart at extremity. In his raw-boned hungry passage, he needs what anyone needs—safety, warmth, nourishment, a place, and people who care about you, which explains why when the book ends Jeff has moved inside you.

I love this book. Gary Lilley’s poems are like the best blues. They conjure up one indelible image after another, and pack a hell of an emotional punch.

To call Gary Copeland Lilley among our best blues poets is to call him among the most forthright and versatile poets working today. His poems are meditations on the breaks and bonds of love and time. His poems are duels and dances with death. Gary Copeland Lilley’s poems are equal to prayer. This book is the spiritual blues of a restless poet and the restless poetry of a spiritual bluesman. Raven on the Moaners’ Bench is a work of inimitable expressiveness.