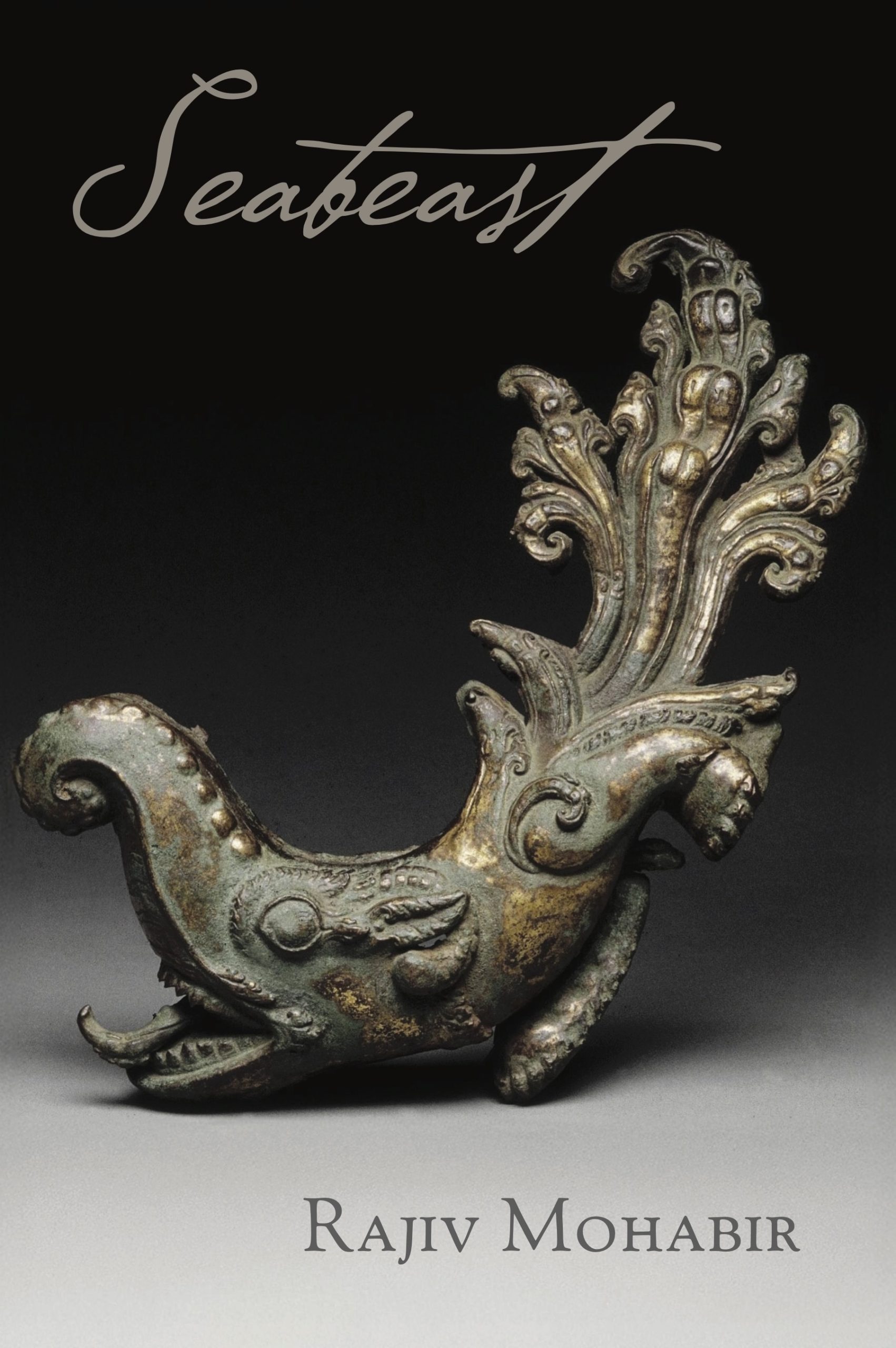

paper • 120 pages • 17.95

ISBN: 978-1-961897-48-9

eISBN: 978-1-961897-49-6

September 2025 • Poetry

Organized as an alphabetical bestiary, Seabeast lyrically catalogues whale species by common name and behaviors, resulting in a poetic compendium that defies pathetic fallacy even as it sings the similarities between homo sapiens and the marine mammoths that have long captured our fascination. In his fifth full-length collection, Rajiv Mohabir winds together the threads of cetacean evolution, natural history, animal migration, and human culture and colonization as they concern the endurance of all species. In anthropomorphizing these complex mammals, Mohabir argues, we overwrite and erase their sublime difference and selfhood, their distinct and separate experience of embodiment; yet, in refusing to recognize the familiarities of whale behavior and social patterns, we subjugate these magnificent creatures, affirming a hierarchy that establishes anything inhuman as inherently less than human and enabling cruelty toward all manner of living things.

Mohabir’s language ingeniously plumbs the depths, illustrating how the objectification fundamental to the construction and preservation of animal taxonomy mirrors the internecine violence of humankind on both a broad and intimate scale. “We were misnamed / again and again: first Hindu, / then Hindoo, then Indian, then / Coolie, all subhuman / much like this precursory cetacean / of the Eocene, named / in Latin great lizard— / anguilliform, what to make / of twist and tear, teeth / gnashing sharks and durodons / into pulp, judged by fossilized / gouges in enamel and finger / holes on skulls?”

Through the invention of race, the conquest and consumption of land, and the cultural amnesia enforced on the subaltern, imperialism threatens human survival on this planet just as we have misunderstood, taken captive, and hunted whales nearly to extinction. Meditating on the results of genetic testing, Mohabir details how, like his white ex-spouse’s “ancestors / from northern Germany / played bone flutes / for their dead at gravesites,” a lab “one day exhumed” them all “in perfect pentatonic scales.” Meanwhile, he wonders what of his Indo-Caribbean heritage, complicated by the obfuscating forces of indenture, ethnic oppression, and frequent relocation, “can be revived” from this “wastebasket taxon, / us unnamed hoard of no future?” Of the Irrawaddy Dolphin once “known for / herding shoals of fish / for fisherfolk / in whose nets / they now drown,” Mohabir observes that “learning human / language opens you // to betrayal.” “Trust me,” he urges, “though I am no // hairless dolphin— / I once had a husband.” Standing at the confluence of these prehistoric, mythological, and contemporary tributaries feeding our attitude toward whales, Mohabir asks, who is the seabeast, really? The namer or the named? The answer prompts us to see that, if we recognize the legacy of human barbarism in the whale’s long history with us, we can also locate a new reserve of resilience and survival. It is their example Mohabir uses, not the “bright honey” of their blubber that once would “fuel lanterns,” to power his own spiritual refortification. “Maybe I will, from filling my lungs, blood / rushing to my core, / into a finned thing, / transform.”

Minke Whale

Balaenoptera acutorostrata

The most abundant rorqual

arrow shaped, scientists now find

to rumble, growl, groan, grunt.

You can listen on the internet,

how whaling has changed,

they are of least concern.

Once mistaken for fin or blue,

their meat is most plentiful

hanging behind glass cases,

songless. Give a white man a knife,

a lance with exploding tip,

a star or shield-shaped badge—

Who won’t he kill?

Seabeast reminds us that naming is never an innocent project. As one speaker declares: “There is no ‘true’ of any order.” So what drives the impulse to catalogue human and beyond-human bodies? How do we refine or refuse the catalogue? Must we keep losing each other like this? Seabeast is another intelligent collection from one of our most necessary poets. I’ve read and re-read these poems and can’t stop thinking about what remains after discovery, desire, and death. Rajiv Mohabir is an exquisite poet. His poems will move through you like a strong current.

Seabeast, Rajiv Mohabir’s remarkable fifth collection, is a marvel of synthesis: a study in cetacean evolution becomes—through astonishing and unforgettable turns toward the human—a deeply intimate personal portrait. These nimble, strangely affecting poems weave together, seamlessly, extinct, mythological, and living sea creatures, cruising in public restrooms, an estranged brother, and a dissolved marriage, as if to remind us that everything is inside everything, everyone a part of everyone, especially when, in bigotry, rage, or shame, we presume or desire otherwise. Seabeast is a profound, healing, and deeply humane book to read and read again.

In Seabeast, our shared climate-grief finds a translator who swims through heartache, hauling the mute language of loss like a whale-calf or broken love. In seeking ancestral resemblances across the shores that bind us to a solipsistic affection for our own species, these poems expand what kith can be, helping me imagine what transcends the transactional co-dependence between species. His poems seem to argue that we should care for endings—of species, of love, of relationships—just as we have cared for their beginnings so that we can learn to adore again the thing washed to shore like it were a life still wrapped around our hips. This, I learn from Rajiv’s book, is the most “gay impulse.” Rajiv Mohabir has produced a collection that enacts a refusal to be a single, legible body. It extends an invitation for each of us to be a shoal, a teeming multitude swimming against the current of climate amnesia.