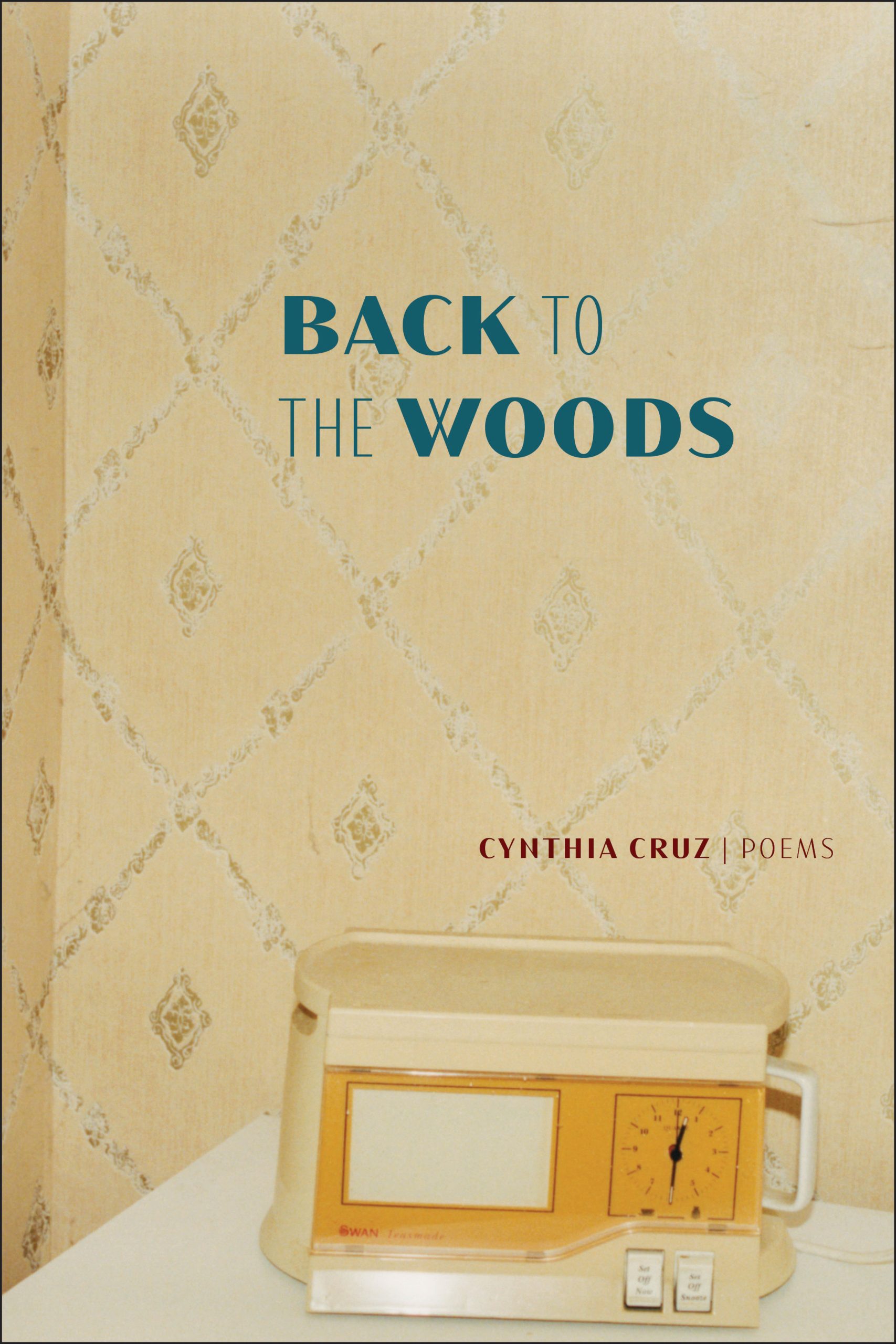

paper • 74 pages • 17.95

ISBN: 978-1-954245-64-8

eISBN: 978-1-954245-65-5

September 2023 • Poetry

Reviewed by Publishers Weekly

National Book Critics Circle Award Winner Cynthia Cruz reevaluates the paradox of the death drive in her eighth collection of poetry, Back to the Woods. Could it be that in ceaselessly snuffing ourselves out we are, in fact, trying to survive? In “Shine,” Cruz’s speaker attests that “if [she] had a home, it would be // a still in a film / where the sound / got jammed.” This book inhabits the silence of the empty orchestra pit, facing “dread, and its many / instruments of sorrow.” The quiet asks, “Did you love this world / and did this world / not love you?” We return to the site of our suffering, we perform the symphony of all our old injuries, to master what has broken us. To make possible the future, we retreat into the past. “I don’t know / the ending. // I don’t know anything,” our speaker insists, but she follows the wind’s off-kilter song of “winter / in the pines” and “the dissonance / of siskins.” Cruz heeds the urgency of our wandering, the mandate that we must get back to the woods, not simply for the forest to devour us — she recognizes in the oblivion “flooding out / from its spiral branches” an impossible promise. At the tree line, we might vanish to begin again.

“Dark Register”

If you leave,

he said,

keep who you are.

Don’t let the world

and its desires

ruin you.

But after the dream

comes the habit.

And no way to fix it.

What is gone

cannot be put back.

Damage

from the inside.

What I have become

is warmed over

with that now

ancient dream.

What I was

is vanished.

I came back home

but I came back

gone.

Cynthia Cruz’s Hotel Oblivion is a harrowing noir, hypnotic in the same way the dull thud of the pulse, from inside pain, can hypnotize. This is a self-portrait of the self that exists—in flashes—in the interstices between what we call the body, what we call the mind, and what we call art (or the study of art, the regard we maintain for art as a human project). Unica Zürn and Jean Genet are the presiding elders of this doubled journey across damaged selfhood and Mitteleuropa. “The mind,” Cruz avers, “is just a dumb machine / that makes small traces,” poem by poem. “And I have begun now to imagine,” Cruz ventures, “what it might be like / to make art entirely / in solitude, to finally / enter the work, and become / what I have been for so many years / afraid of: the space between, the place / of magnificent, though mostly / terrifying, silence.”