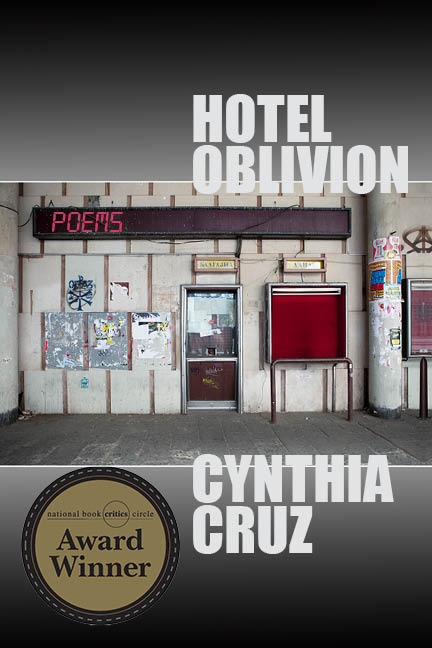

paper • 120 pages • 16.95

ISBN: 978-1-954245-11-2

eISBN: 978-1-954245-19-8

February 2022 • Poetry

Received a starred review in Publishers Weekly

A specter, haunting the edges of society: because neoliberalism insists there are no social classes, thus, there is no working class, the main subject of Hotel Oblivion, a working class subject, does not exist. With no access to a past, she has no home, no history, no memory. And yet, despite all this, she will not assimilate. Instead, this book chronicles the subject’s repeated attempts at locating an exit from capitalist society via acts of negative freedom and through engagement with the death drive, whose aim is complete destruction in order to begin all over again. In the end, of course, the only true exit and only possibility for emancipation for the working class subject is through a return to one’s self. In Hotel Oblivion, through a series of fragments and interrelated poems, Cruz resists invisibilizing forces, undergoing numerous attempts at transfiguration in a concerted effort to escape her fate.

What is a fragment, a found

postcard, ephemera, ruin or a photograph.

For example: Doris Peter’s “Children

collecting scrap metal, George Washington Street,

1997,” Russian. Or a Che Guevara montage

on dream board in the sweetshop, Neukölln.

Why glean, why assemble, or

how does accumulation keep.

How does getting it all down

do the same work as making. And how

is the gluing of words together

not unlike taking something beautiful apart.

In the afternoon, on Saturday,

I bought a pale blue dress from Humana

and walked alone, home, in it,

through the parades of my emptiness.

Cynthia Cruz’s Hotel Oblivion is a harrowing noir, hypnotic in the same way the dull thud of the pulse, from inside pain, can hypnotize. This is a self-portrait of the self that exists—in flashes—in the interstices between what we call the body, what we call the mind, and what we call art (or the study of art, the regard we maintain for art as a human project). Unica Zürn and Jean Genet are the presiding elders of this doubled journey across damaged selfhood and Mitteleuropa. ‘The mind,’ Cruz avers, ‘is just a dumb machine / that makes small traces,’ poem by poem. ‘And I have begun now to imagine,’ Cruz ventures, ‘what it might be like / to make art entirely / in solitude, to finally / enter the work, and become / what I have been for so many years / afraid of: the space between, the place / of magnificent, though mostly / terrifying, silence.’

Hélène Cixous said, ‘The writers I love are descenders, explorers of the lowest and deepest,’ and Cynthia Cruz is a master of descent. Her exquisite new collection, Hotel Oblivion, emerges from ‘the terrible intimacy / of the mouth’ in the form of letters and fragments composed in isolation across hotel rooms in Warsaw, Berlin, and Belgrade. These rooms double as art studios and prisons, as well as rooms of the mind, in which Cruz’s speaker remembers, unknows, and reaches toward a ‘self- / made language’ which is ‘not unlike taking something beautiful apart.’ Hotel Oblivion is a compulsive read—it rivets with its obsessiveness, world-building, and refusal to sublimate: ‘Now the poems are coming like gray rings / of memory. Or an endless series of Polaroids.’ Dear reader, when I got to the end, I wanted to begin again.

“Cruz offers in Hotel Oblivion a deeply felt excavation of hierarchically damaging language….Cruz expands and transcends the interiority of the lyrical ‘I’, achieving a fresh and vital depiction of the I-Thou relationship in poetry. This is a wholly original book, one in which Cruz’s luminous music attains a self-realized language singing out of the disaster.”