paper • 138 pages • 17.95

ISBN: 978-1-954245-84-6

eISBN: 978-1-954245-85-3

March 2024 • Poetry

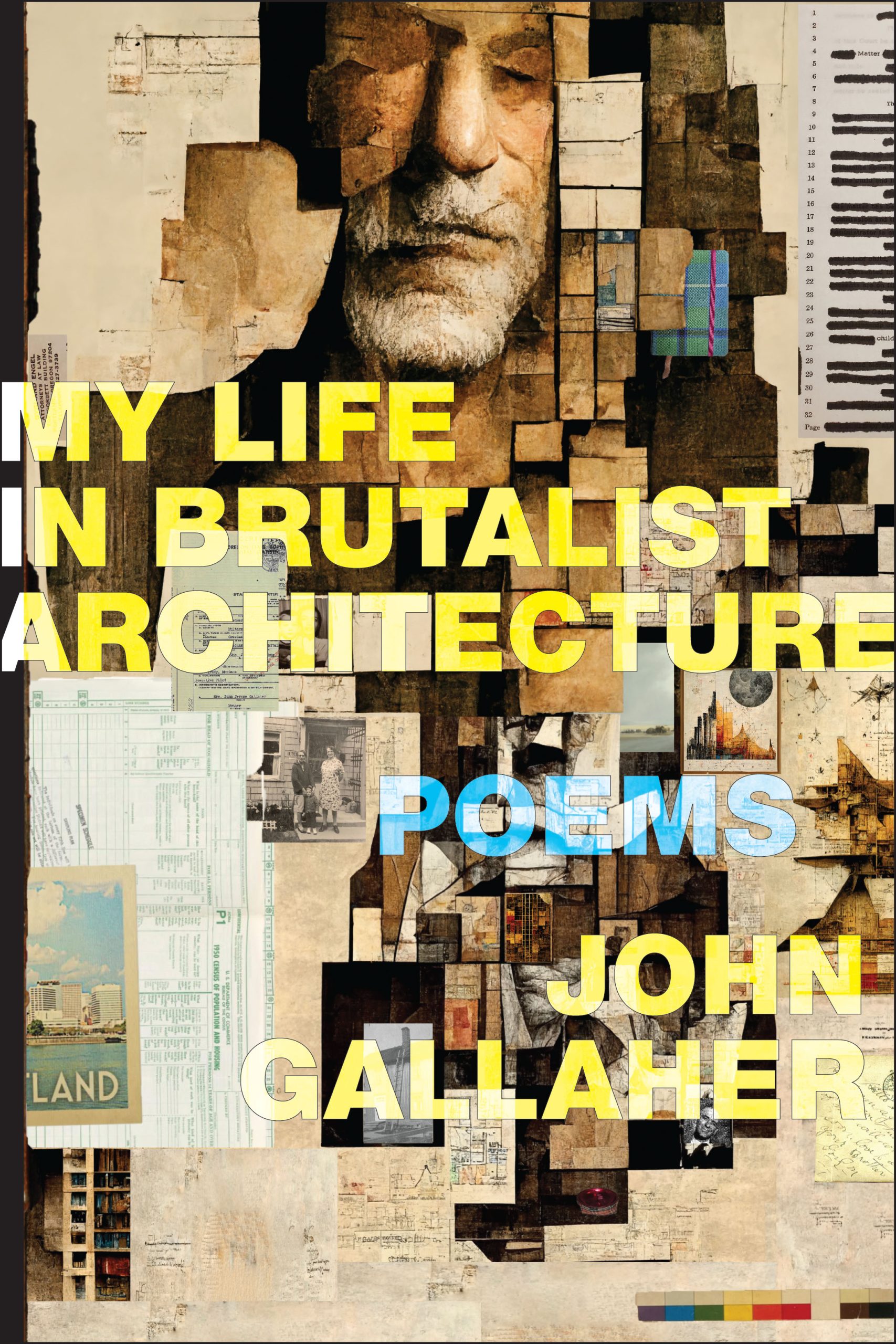

As John Gallaher prefaces this book, “It should have been an easy story to sort out, but it took fifty years.” My Life in Brutalist Architecture confronts the truth of the author’s adoption after a lifetime of concealment and deceptions with lucid candor, startling humor, and implacable grief. Approaching identity and family history as a deliberate architecture, Gallaher’s poems illuminate how a simple exterior can obscure the structural bricolage and emotional complexity of its inner rooms. This collection explores – and mourns – the kaleidoscopic iterations of potential selves as prismed through our understanding of the past, a shifting light parsed by facts, memories, and a family’s own mythology. The agonizing beauty of My Life in Brutalist Architecture is its full embrace of doubt, a jack that makes space for repair even as it wrenches one apart. After his daughter’s birth, the author considers the only picture of himself before the adoption, captioned “Marty, nine mos.” In legal documentation, in the photographic archive, this child no longer exists. “I appear next as John, three-and- a-half,” Gallaher writes, “and Marty disappears, a ghost name.” “And so, then, what does the self consist of?” he asks. The answer is, necessarily, no answer. “The theme is time. The theme is unspooling,” Gallaher summarizes, testifying to a story’s inability to recover the past or isolate its meaning. Equal parts reckoning and apologia, Gallaher’s latest work disrupts the notion that what you don’t know can’t hurt you, attesting to the irrevocable harm of silence, while offering mercy in its recognition of our guardians as deeply flawed conduits of care. Referencing Vitruvius’s foundational elements of architecture (firmitas, utilitas, and venustas, or solidity, usefulness, and beauty), Gallaher fuses an elegy and an ode to family when he writes “that in the third principle of architecture, / they bathe you and feed you. You won’t remember. // And they know this.” Gallaher’s lyricism encapsulates this, humanity’s consummate tragedy and profoundest grace – that love, even when forgotten, persists.

From “The Aura Homily”

I took the Myers-Briggs test on my lunch break today,

and I’m an INTP, the laziest and most condescending

of the sixteen personality types, also the most likely type

to say black is my favorite color. Maybe I could call that

my aura. Adoptees are good at making stuff up.

Nuns, priests, and the void wear black. Maybe someone

would see me and think I’m a nun, priest, or the void. I mean,

I don’t even believe in auras. And now, look at me.

Maybe, being adopted, my aura is lost in transit, UPS color,

wrong address color. Maybe my aura’s a color that’s not been invented yet,

a secret color, like how Homer couldn’t see the color blue,

so the ocean was wine. Maybe it said, “Je est an autre” as it passed

and no one at this party speaks French, or the cortege

took a wrong turn, and said, sure, this place looks as good as any.

In his new poetry collection, John Gallaher writes, “How about you? You’ve had a mouth full of clouds too. / You’ve wanted to know things no one wants to tell you.” I wish I could reach beyond the limits of a short comment to fully express how moving I’ve found John Gallaher’s My Life In Brutalist Architecture. The Great Subject here is adoption, especially for those of us set on the path of this life defining mystery during the “great baby scoop era” between 1945-1972. As Gallaher states it, “The theme is secrets. The theme is each new morning / absolves itself of last night’s stars.” Beyond the specific circumstances of that recent era in which infants were a hard currency exchanged with the utmost secrecy (both state and family), this is a book that illuminates how we design and operate the myths of ourselves, those that necessarily evolve, those that are fixed for anyone at birth. It’s an incredible book.

John Gallaher’s My Life in Brutalist Architecture is an argument for the continuing vitality of the poetic sequence-more than that, it is evidence that the poetic sequence can be utilized to tell stories as effectively and powerfully as the novel and the memoir. But My Life in Brutalist Architecture is better than a novel, better than a memoir, because it is poetry. Poetry leaves spaces for the reader’s imaginative participation in the story, and Gallaher’s lyricism, both unassuming and perfected, ignites the reader’s imagination even as the reader takes in Gallaher’s difficult story, beautifully told.