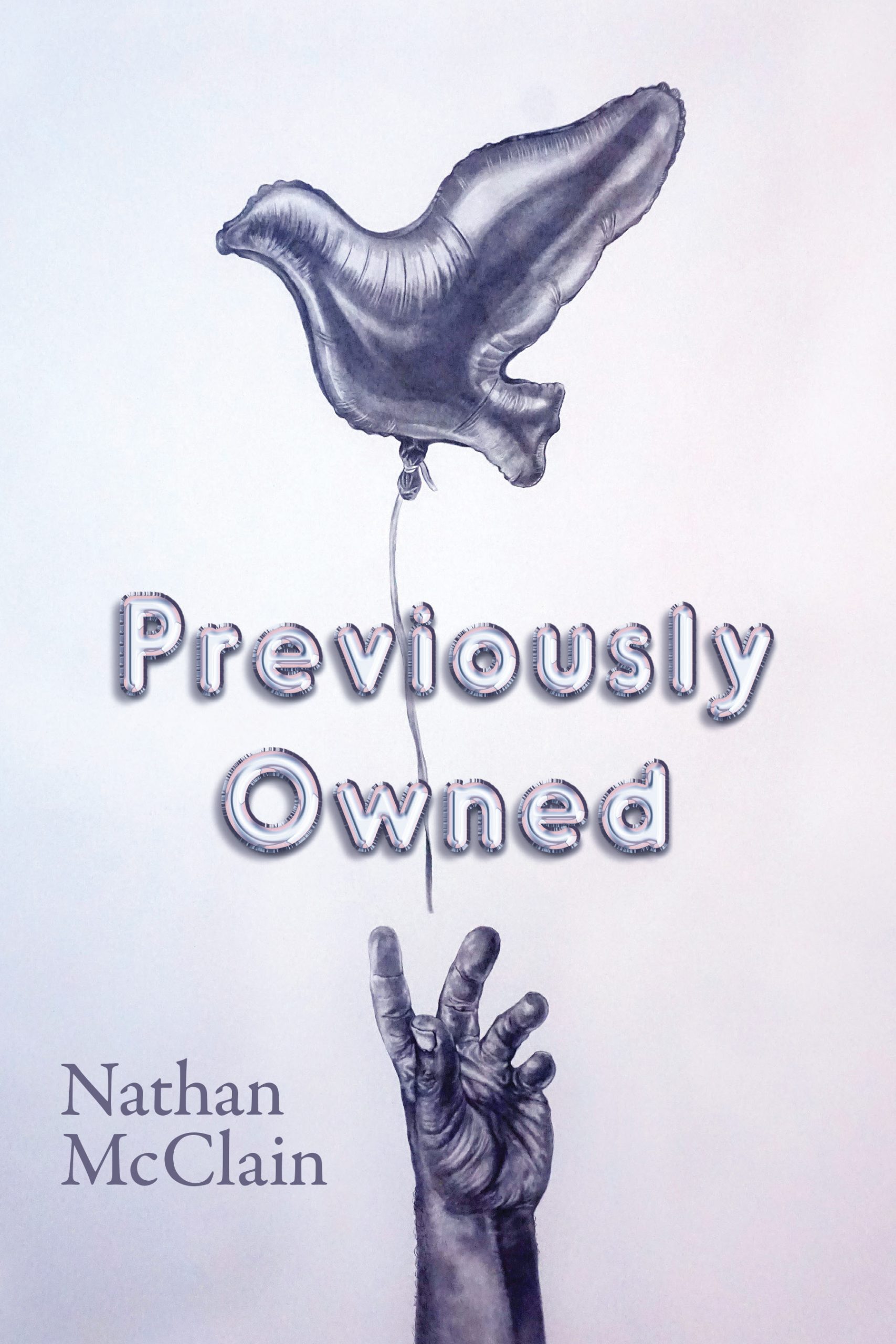

paper • 120 pages • 17.95

ISBN: 978-1-954245-26-6

eISBN:978-1-954245-39-6

September 2022 • Poetry

In his daring sophomore collection, Nathan McClain interrogates his speaker’s American heritage, history, and responsibility. Investigating myth, popular culture, governance and more, Previously Owned connects a villanelle cataloging Sisyphus’s circular workflow to a Die Hard persona poem critiquing police brutality and joins complex pastorals to the stunning sequence entitled “They said I was an alternate,” which recounts the author’s experience serving on jury duty. Though McClain’s muscular lyric explores a wide range of topics, the intensity of his attention and the profundity of his care remain constant — the final page describes a young girl in a diner, ringing the bell at the host stand, “just to hear it sing, the same / song, the only song // it knows.” Insofar as this collection scrutinizes one’s own culpability and responsibility in this country, interested in the natural world and beauty, as well as what beauty distracts us from, it does so in the hopes of reimagining inheritance, of leaving our children a different song.

“What You Call It,” from Previously Owned

…The peach was simply a peach,

and there for the taking,

which is often said of an object that has gone

unwatched for too long, susceptible

to trespass, which happens

first in the mind, and happened first

because of fruit,

or so says The Good Book

if you believe in such things. Knowledge,

which a poet once called “historical,” too

a trespassing of sorts, the proof of which

perhaps best shown in how one

might punish a slave who had been

taught to read the word beauty or toil

or rest, secretly, and by firelight.

There are things nearly impossible

to forget, having so trespassed…

In Previously Owned, America’s dark history is not quaintly rooted in the past, but dangerously ever-present. ‘And what / have you learned from / standing here so long / examining pain?’ Nathan McClain questions in the opening poem ‘Boy Pulling a Thorn from His Foot’—not just the reader—himself as witness. If Scale, his first collection, can be said to be anchored in domestic space, then Previously Owned expands the architecture of that domestic space to include Country and the country. The ways in which McClain troubles the pastoral and peripatetic traditions thrills me: ‘I’ve never actually seen a moose, / only signs warning of moose, / and NO PASSING ZONE signs’ (‘Where the View Was Clearer’); and of the fireflies in ‘Now that I live in this part of the country,’ ‘look, they / flash the way hazard / lights sometimes flash… / and I might have said, no, / don’t they seem to pulse / with the glow of old / grievances?’ This book is a triumph and will be talked about for years. Nathan McClain is one of the most daring poets I know.

The opening poem of Nathan McClain’s Previously Owned operates like the legend of a map, a key to the book’s existential topography. The poem’s presenting subject is a Roman sculpture of a boy pulling a thorn from his foot, or ‘not pulling / rather, about to pull.’ McClain addresses the self via the second person, and draws in the reader, too, as observer: ‘and here you / are, looking,’ witness to the boy’s ‘insistent grief.’ ‘And what // have you learned from / standing here so long examining pain?’ Previously Owned exists in this incremental space—the about to pull, the almost, the grief, the tenderness, the examination, and the distance. It’s a masterstroke in a masterful collection, in which a speaker of a nuanced intelligence and lush interiority reflects upon the American landscape, its pastoral and judicial and historical duplicity entwined with racial alienation and violence. McClain has written a collection of sculptural artfulness—through which the thorn of grief thrums still.

Nathan McClain’s Previously Owned is no-nonsense, meat and potatoes, good gotdam poetry. Careful readers will appreciate how exquisitely crafted are his lines, how resonant his images, how thoughtful his progressions. What’s more, McClain’s second volume shows us a writer who, like Robert Hayden before him, neither ignores nor is encumbered by his country’s complicated history. His topics range widely and the whole of the human landscape—physical, psychological—is his, and ours, for the roaming.