paper • 72 pages • 16.95

ISBN-13: 978-1-945588-52-5

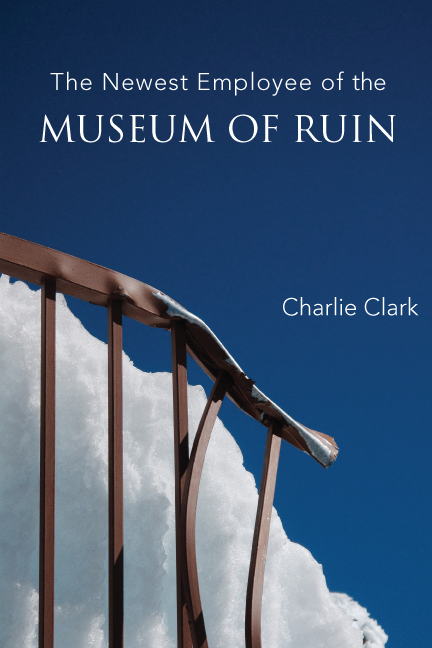

In The Newest Employee of the Museum of Ruin, poet Charlie Clark interrogates masculinity, the pastoral, the lasting inheritance of one’s lineage, and the mysterious every day. His speaker, ever aware of impending ruin, experiences a landscape colored by anxiety. But his speaker is also self-aware, curious and trying to refrain from too much self-judgement: “I am sorry / for this cruel wish, but I want my life to outlast / bitterness.” The speaker turns over and over the materials of culture, asking what pleasure it creates, replicates, diminishes or destroys. When the tension runs too high, the poet creates moments of relief — “Suffering is not a philosophy any more than rain is.” Readers follow a speaker searching for ways to enjoy living within a damaged and declining world. Through wide-eyed poems rich in image, the beautiful, the plain, the ugly coexist in a debut collection 15 years in the making.

Amateur Hour (What Do Sad Songs Remind You Of?)

The clouds here are beautiful in the manner of my wife’s hands.

They are pleasures with strange limits, and change color quickly.

In this way, they are like most beautiful things. Take songs.

In the car, when my wife turns the volume knob it’s to make the sadness louder.

During the commercials or the jockey chatter after, I worry I’m depressed.

But just because I might be depressed doesn’t mean I’m serious.

To be serious is to have something unwavering inside you.

And, oh, how I waver. I’d write anything so long as it was beautiful.

It’s beautiful to touch either of my wife’s hands.

My wife’s hands are warm as flagstones set out beneath the sun.

When I touch them the ringing in my ears becomes the tuning of viola strings.

I think it was something like this that made Andre Breton write “Free Union.”

But his enumerations get tedious. I’ll limit mine to my wife’s hands, then.

My wife’s hands invented the word abode. When she folds them,

my wife’s hands are tighter than the onion where all time goes.

One day it snowed and my wife put her hands inside the snow.

They came out flush as the blood in the heart of a swan.

When she put them to my face I could not feel my tongue.

What strange, off-kilter, brilliant poems Charlie Clark has written. The inhabitants of this book live in worlds that mostly resemble our own, if it weren’t for those men sprouting wings, or the rings wrenched around the moon, or that sixteen-year-old boy scrawling Kierkegaard on the bathroom wall. Witty, inventive, and graceful, these poems crackle with energy. But beneath that energy lives the real stuff of poetry—longing, fear, rage, lovely suffering—keenly felt, made whole in language.

Charlie Clark’s remarkable The Newest Employee of the Museum of Ruin is a book so full of ‘fresh, blunt wonder’ and ‘compilations’ of delicious noticings, of energetic reports, so full of the passion, movement, and invention Berryman required of poetry that I felt as if I truly was experiencing the world in a new way. Clark’s idiom is dexterously off-kilter, his images rich and brightly focused, and his ear pitched precisely to the way we think as well as hear. But perhaps what I admire most about Clark’s museum of ruin is its vast inventory of affection which he’s created out of a rare and infectious love of the world, a world in which he asks ‘Gentle, brightness’ to burn him ‘into singing.’