paper • 134 pages • 19.95

ISBN-13: 978-1-945588-55-6

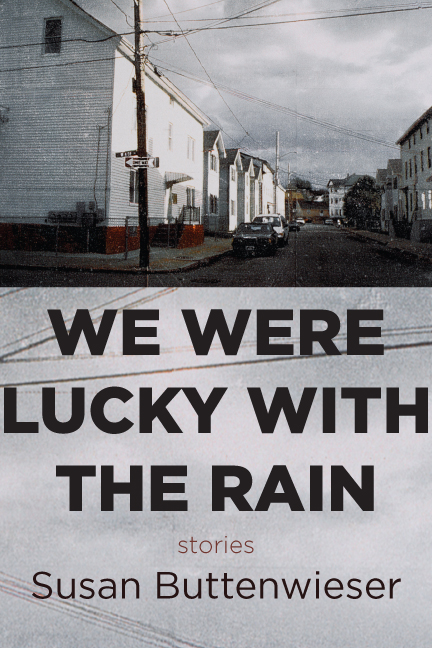

The characters inhabiting Susan Buttenwieser’s debut story collection We Were Lucky with the Rain stand at the margin of society, often perched on the knife’s edge of economic disaster. Her characters cope with emotional and physical isolation as they try to build, keep, or renew family structures. An older brother drops out of college and tries to keep his youngest sister from ending up like the rest of the family. A father shields his daughters from their mother’s erratic behavior, while his daughters struggle to understand their anxiety and anger. An uncle copes with his helplessness to protect his nephew. No quick fixes, no miracle cures await the people within these stories. This is fiction devoted to realism. And Buttenwieser’s compassionate narrator refuses to look away during their most vulnerable trials. A remarkable debut collection.

Excerpt from “We Were Lucky with the Rain”

Lacey can’t resist spying on her parents when they fight. Which happens whenever her mother has disappeared for a few hours or, occasionally, the entire evening. She lies flat on the wooden floor of their upstairs hallway, peering through the banister at her parents yelling at each other in the living room below.

Her father wants to know where her mother has been and why she didn’t pick up Lacey from her piano lesson this afternoon, or her younger sister, Eileen, after school.

“I told you this morning that I was going to this Mom lunch thing at Hoolihan’s. So I was late, okay?” Lacey’s mother throws her purse onto the floor. Only her legs are visible, jutting out from underneath a red dress, roaming around the living room. She bumps into the coffee table, left ankle buckling.

“You weren’t late, you didn’t show up. You didn’t answer your phone. We had no idea where you were. And now you’re a complete mess.” Her father’s voice goes up an octave. “You could have killed someone, you know.”

Her mother starts laughing. “Jesus, relax. I took a cab.”

“Then where is the car, goddamn it?”

If Lacey tilts her head a certain way, she can see her father’s slippers pacing back and forth. She strokes her fraying rope bracelet that she got at her school’s Fall Festival. Her fingers always work their way to its soft underside whenever she’s waiting for her turn to bat for her softball team or perform in a piano recital.

“The car is fine, alright?” her mother says. “I left it in the parking lot at that Star Market by Hoolihan’s. You know, the one in Tremont Square.”

“It’s not fine. It won’t be fine. You can’t leave the car there overnight. It’s going to get towed!” Her father’s slippers stop moving. Then he stomps his left foot on the floor and throws a sofa cushion out into the hallway. A table lamp crashes to the floor and her mother shouts at him to Stop it, just stop it.

Lacey can’t understand how Eileen always sleeps through their parents’ arguments, which often involve things being broken. A few weeks ago, her mother hurled a bottle of red wine against the front door. Another time it was plates. She’s also thrown glasses, shoes, and once a dining room chair. But her father always cleans it all up, and in the morning, there is never a trace of the mess, not even one thing out of place anywhere.

Unsettling things happen in Susan Buttenwieser’s debut collection, We Were Lucky with the Rain. A website content monitor stalks a suburban housewife and her daughters. A teenager loses track of her kid sister while escaped convicts are on the loose. A family eats its last supper before the father begins a prison sentence. A motel housekeeper’s coworker does—or doesn’t—discover a gun, a backpack full of money, and half a finger in a closet. But despite the sometimes-dark premises, this is a collection full of light and hope, where grace arrives in tender moments of unexpected kindness, all of it rendered in quiet, pitch-perfect prose. We Were Lucky with the Rain left me feeling lucky to have discovered Buttenwieser’s luminous fictional voice.

Susan Buttenwieser’s stories are sharp, funny, surprising, and immensely satisfying. They’re also a little bit wince-inducing because she’s able (and willing) to expose the emotional and behavioral underbelly of her characters, and her characters are you and me. I would follow this writer anywhere.

Susan Buttenwieser is wise, out-loud funny, awe-inspiringly empathic, and the wielder of a marvelously dangerous and whetted wit. Buy, read and revel; Buttenwieser is the best there is.

…Buttenwieser’s sketches are more like pathology slides of the human condition than snapshots of happy family picnics.