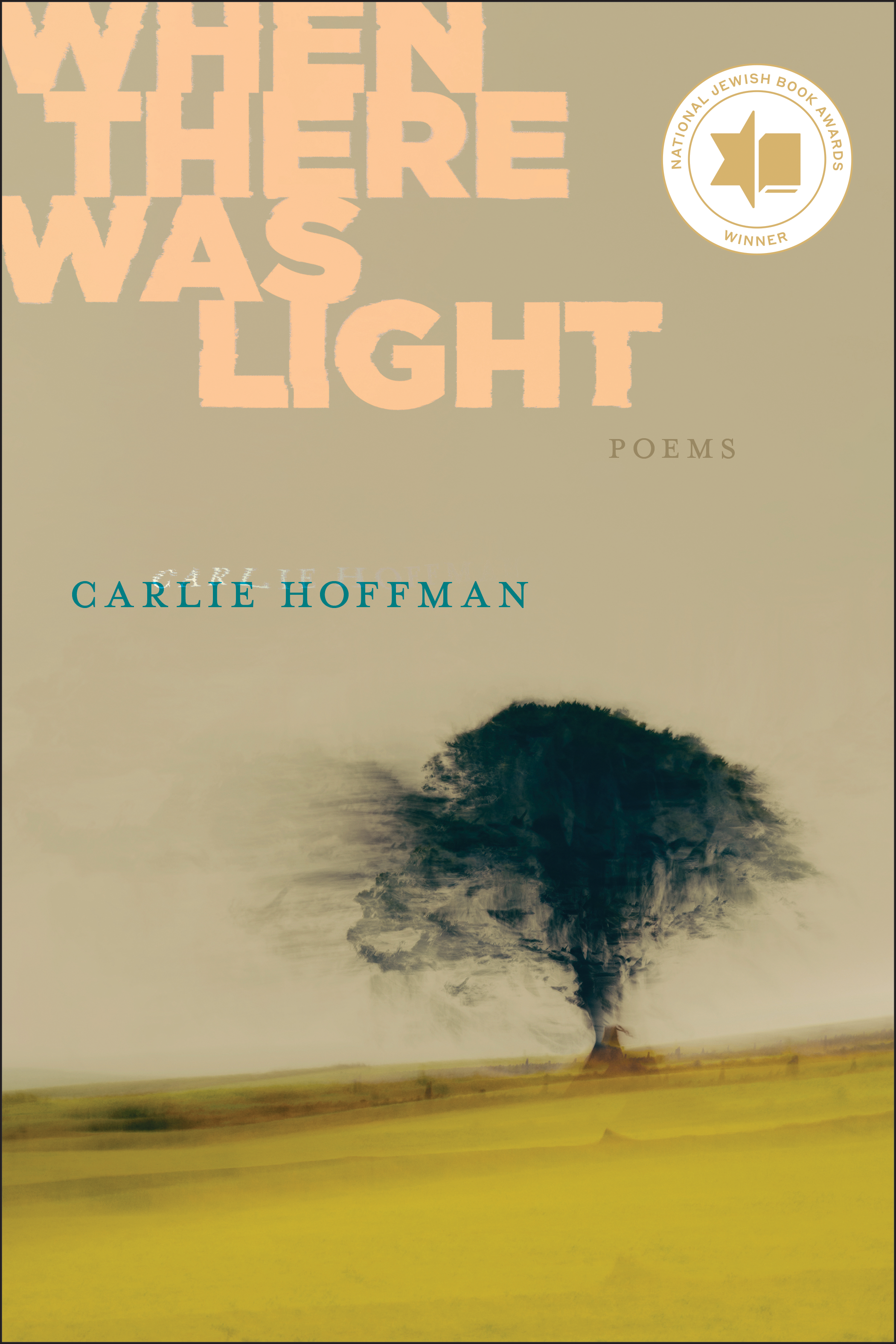

paper • 80 pages • 17.95

ISBN: 978-1-954245-42-6

eISBN: 978-1-954245-43-3

March 2023 • Poetry

Winner of the National Jewish Book Award in Poetry

While Hoffman’s debut collection interrogated the mythos built around grief, inhabiting an Alaska of the mind, her stunning sophomore collection When There Was Light looks at the past for what it was. These poems map out a topography where global movements of diaspora and war live alongside personal reckonings: a house’s foreclosure, parents’ divorce, the indelible night spent drunk with a best friend “[lying] down inside a chronic row of corn.” Here, her father’s voice “is the stray dog barking / at the snow, believing the little strawberries grow wilder / against a field.” In these pages, she points to Russia and Poland and Germany, saying, “It was / another time. My people / another time. The synagogues burn decades / of new snow.” The brilliance of this collection illuminates the relationship between memory and language; “another time” means different, back then, gone and lost to us, and it means over and over, always, again. With this linguistic dexterity and lyrical tenderness, Hoffman’s work bridges private and public histories, reminding us of the years cloaked in shadows and the years when there was light.

Every season is good for killing girls,

the seaweed-black night foaming

with stars—

a plaque of women’s names.

Before Mary’s a whore,

a baby is placed in the frozen bird

of her lap, the dignity in being.

Every place that hurts you

is the season where the sun bursts

like salmon on fire. Think

of Eve shivering naked beneath the alder

watching God get angry—

is it anger or is it grief—all of us doing

what we’ve been trained to do.

Carlie Hoffman’s poems see pain, danger, regret, remorse, mercy in ways other documentation cannot. Sometimes a balm, other times a warning, often a record, most often all at once. Here is how Hoffman opens a few poems: “February, worst month, The last time, When I was suffering, I’ve lost you again, It seems to me a blessing, Every season is good for killing girls.” Hoffman’s poems accept their fierce conflicts and struggle. Her reaching for a way to say in words never ends. Near the book’s end Hoffman asks a question. “Will I ever stop being angry / for never hearing my family’s language?” Imagine how many ways to take that question. In another poem Hoffman says, “Somehow, American,” and it sums up an almost unbearable too much. This is a beautiful book, willing to look with love, the kind poetry provides, deep into what our families do and mean to us, what they give us, what they take away.

“It’s important to walk like this: through the places where the vanished people of our lives have walked,” writes Carlie Hoffman in her astonishing new collection, When There Was Light. In poems resounding with absence and loss, Hoffman journeys through Poland and Germany to a farm in upstate New York to investigate her roots — roots shattered by war, displacement and ‘the violet, ancient noise’ of a family’s silence. In image after throat-grabbing image, she makes the damage to successive generations visceral. A photo album glows “like a severed shoulder of a man.” Of the languages lost to her, she writes, “my beheaded tongue Hebrew tongue Russian tongue I comprehend nothing…” When There Was Light is a deeply moving personal reckoning. But its themes are universal: history, memory, identity, the struggle to understand our lives. “The world has so many rooms,” she writes, “it’s impossible to pinpoint where mine begins.”

I am in awe of the way in which in Carlie Hoffman’s poetry image and word espouse themselves, braid each other into not a surrealist image, but into what Jerome Rothenberg once called a “deep image.” This comes from a very clear-eyed, deep-eared stillness she is able to work from even if or when at the center of this / her world’s turmoil. Or as she puts it, “Girl at the threshold / catching the light with her hands.” This is quest-writing, the quest of poetry, so well laid out in these lines: “There must be a word for the lack / of words for the things we have felt all / our lives, but couldn’t name.”