paper • 124 pages • 17.95

ISBN: 978-1-954245-44-0

eISBN: 978-1-954245-45-7

March 2023 • Poetry

Longlisted for the PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry

Reviewed in The Rumpus

Reviewed in RHINO

Reviewed in Poetry Foundation’s Harriet Reads

Reviewed in Washington Independent Review of Books

Reviewed in The Dawn Review

Reviewed in The Massachusetts Review

Interviewed by Erica Abbott in Write or Die Magazine

Interviewed by Cheryl Klein in Mutha Magazine

Interviewed by Alexa Luborsky in Poetry Northwest

Featured in The Slowdown podcast with Major Jackson

Featured in WNYC’s All of It podcast with Alison Stewart

Featured in Ms. Magazine‘s Best Poetry of 2023 list

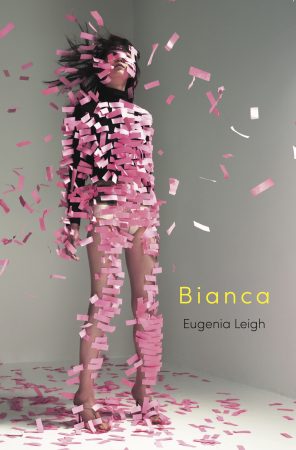

“I thought I forgave you,” Eugenia Leigh tells the specter of her father in Bianca. “Then I took root and became / someone’s mother.” Leigh’s gripping second collection introduces us to a woman managing marriage, motherhood, and mental illness as her childhood abuse resurfaces in the light of “this honeyed life.” Leigh strives to reconcile the disconnect between her past and her present as she confronts the inherited violence mired in the body’s history. As she “choose[s] to be tender to [her] child—a choice / [her] mangled brain makes each day,” memories arise, asking the mother in her to tend, also, to the girl she once was. Thus, we meet her manic alter ego, whose history becomes the gospel of Bianca: “We all called her Bianca. My fever, my havoc, my tilt.” These poems recover and reconsider Leigh’s girlhood and young adulthood with the added context of PTSD and Bipolar Disorder. They document the labyrinth of a woman breaking free from the cycle of abuse, moving from anger to grief, from self-doubt to self-acceptance. Bianca is ultimately the testimony of one woman’s daily recommitment to this life. To living. “I expected to die much younger than I am now,” Leigh writes, in awe of the strangeness of now, of “every quiet and colossal joy.”

The rest of us,

trembling among our mothers’

bargain trench coats, waited

for Narnia. There, we dreamed

we were the children

of lions. Heirs to our own beds. Safe

in a closet rapturous with centaurs

in symphony with naiads and fauns. And I,

pink and young, swelled like a sinless sun. And I

pretended my father—

who had struck me then shoved me in—

would find my tomb empty

and repent. No, that is the adult talking.

I was a child then. It didn’t matter

what he’d done.

I still wanted to be found.

Bianca is stunning, powerful, a lesson in memory’s resistance to healing. Fiercely honest and a master of line breaks, Eugenia Leigh writes about trauma and mental illness in a way that reminds me that terror can still accompany thriving. Traversing childhood, young adulthood, marriage and new motherhood, Leigh contends with the ways constant survival can keep a person from living and loving. I am more alive and more myself after reading these poems. This is a book I didn’t know I was waiting for.

Eugenia Leigh’s Bianca pierces with its white hot rage and sorrow. With terrifying honesty and lyric precision, Leigh revisits the cyclonic violence her father inflicted upon her and her family and explores the dangers of mental illness when it goes unspoken, untreated, and unnamed. Bianca devastates me.

I hope you read Eugenia Leigh’s Bianca from cover to cover, in one sitting, as I have. In these pages you will travel with a woman — brain, heart, and gut — delving into nightmare and violence to finally retrieve a life of love and motherhood, to accept that life. These poems, which are sometimes a torrent, sometimes a clear evening sky, challenge the reader to witness pain and then reward us with the poet’s relentless search for connection and beauty.

Divided into three sections, Bianca is structured in the shape of an anamnesis. It is both a recollection and a medical history. Getting to know the “million warring citizens” (“Family Medical History”) that live in the poet’s body-city brings an understanding of the “I” and its struggle with a certain erasure of Self, provoked by trauma. A troubled father, a bipolar condition, remembrances of attempts at embracing life after attempting to leave it. “My mother still calls / to ask whether our doors are locked. / Maybe there is no cure for this. The way / the brain bends after trauma / and bends the world with it.” (“June Fourteenth”)…This is what Bianca does with its words.

The book moves from a fear of genetic determinism to a recognition of loved ones who refuse to abandon her, even when “cursed at and punched.” The long poem “Bipolar II Disorder: Second Evaluation (Zuihitsu for Bianca)” introduces the author’s “bipolarity Bianca,” a character blamed for her “fever, [her] havoc, [her] tilt,” for scratching and screaming (“It was a joke”). A husband, a son, friends, sisters, and strangers (including a taxi driver profoundly forgiving of being vomited on) show care for “Bianca,” and eventually lead the text’s “Eugenia” to love her various selves “the way / a father or a mother ought to have loved them. / Them. // Yes, I suppose I do mean me.”

This is not a collection that can simply be read and then put aside. No, we are bearing witness to a true healing here as Leigh peels away essential layers while chronicling her journey through a violent childhood with a mentally ill father, and then into adulthood, where she discovers that she has inherited the bipolar II disorder that haunts her family…Leigh strips bare the concepts of stigma and shame, the harmful fallacy that we should bear our suffering alone and in silence. Not all healing can, or should, be done in isolation, and Leigh’s experience, though deeply personal, is also a collective one she shares with friends, colleagues, and even strangers.

hroughout the collection, the speaker recounts harrowing abuse through jarringly honest confessions, interspersed with obscure metaphors. This mode of recollection mirrors the breakdown and uncertainty that plagues the speaker’s family life– despite having found a space to love, the speaker’s relationships are constantly threatened by the specter of familial trauma, mental disorders, and violence. Bianca teaches us that trauma is never fully escapable: some hide from it, while others grow comfortable with its constant presence.

In a time of natural and political disaster, Leigh’s collection conveys confidence in communal investment toward the future, one that takes action even in the quotidian—to “stick it out for another week”—because what we want is that close.

Bianca portrays the lingering, long-term effects of abuse and mental illness with such beauty, terror, and comprehension…the collection jumps, skips, and hops backwards in time all while steadily tracking, piece by piece, how a person can at last reach the opposite conclusion.